TV images of our cities in flames recalled to me a spring day in 1985, when one American city faced a similar choice between public safety and lawless violence. It started when a nicely dressed middle-aged man and his younger assistant from a local public agency stopped into a corner coffee shop in South Central Los Angeles for a bite to eat.

To their dismay, three young, burly black fellows blocked the entrance to the restaurant. One of them said menacingly, “Y’all aren’t coming in here.”

The assistant held up a portable radio and asked his boss, “Shall I call for some assistance?” “No, that’s okay,” the older gentleman calmly told him. He turned to the young intimidators and declared, “I will be back.”

They walked to their shiny Crown Victoria and drove away toward downtown. On the way, the man remarked that he had grown up here in Los Angeles in Highland Park during the 1930s and ‘40s.

“We used to drive down to that old café all the time. It was so pleasant with nice middle class well-groomed houses and tree-lined streets.

“Everybody in the neighborhoods knew each other and watched out for each other’s kids. Even when I returned home after serving in the Navy during World War II, it was a pleasant place to live and visit.

“But now look at it! If the kind of intimidation we just experienced can happen to us, what must the poor business owners and residents be experiencing?”

So went the conversation between Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates and one of his assistant chiefs that day 35 years ago. Gates walked into his office on the 12th Floor of Parker Center in downtown L.A. and got a certain well-respected sergeant from SWAT on the phone.

The chief related that morning’s incident to this hard-charging Vietnam veteran and issued an order. The sergeant was to tap two SWAT colleagues and, with their help, select 30 officers from across the 18 geographic divisions of the 6500-officer force to comprise a new, specialized gang unit. It would be known as the “Strikeforce” and would report directly to Chief Gates.

Recommended

Trained and led by the three talented SWAT supervisors, Strikeforce went to work using their specialized skills and collective experience along with all other LAPD intelligence resources to identify, locate, and arrest the most notorious and ruthless gangbangers of any ethnic group or geographic location across the city.

The word went out: “If you are raping, robbing, murdering, extorting, committing arson, and generally terrorizing the neighborhoods of our city, we are coming to get you—and there is not a damn thing you can do to stop us!”

I was one of those 30 officers.

From white skinhead gangs in the San Fernando Valley to Hispanic gangs in East LA to Asian gangs in Chinatown and Little Tokyo to black gangs in South Central, we spent the next 90 days hunting down and removing the most violent dangerous criminals from our city.

The haul of illegal weapons, drugs, and stolen goods we recovered in conjunction with these arrests was amazing.

The citizens who owned the homes and businesses that provided us the information to track our suspects quietly thanked us. The victims of the crimes perpetrated by these gang members quietly thanked us.

Chief Gates and the command staff quietly thanked us, slid a nice letter of commendation into our personnel files and sent us back to our patrol divisions.

The gang members and radical activists were not so happy, but there was little they could do. Their bluff had been called. Neighborhoods were getting safer.

For me, it was an honor to serve. It was an honor to stand on the wall and protect all of the citizens of our great city. Democrat or Republican, black, white, Hispanic or Asian, it didn’t matter. Every person’s life in those threatened communities mattered to us in law enforcement—and still matter today.

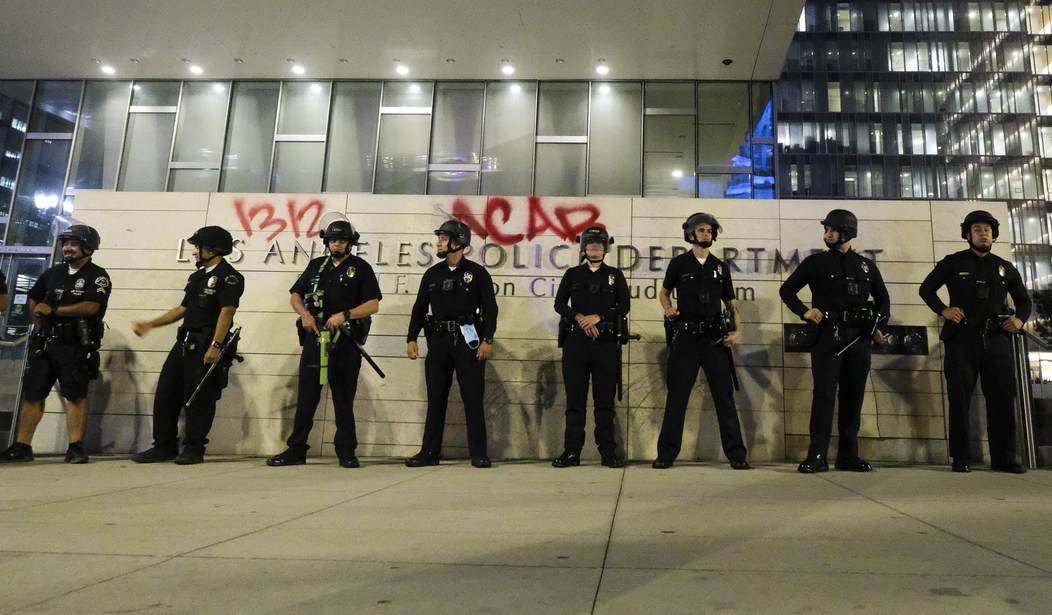

So before we start defunding police departments like LAPD, decision-makers need to talk directly with the business owners and residents who will be most affected by these decisions.

If you need help doing so, let me know. I’ve lived through the “before and after” of a city unprotected from predators and a city protected. There’s no comparison.

Denny Dillard has four decades of experience in law enforcement and homeland security. He now heads Hold Fast America, a Colorado-based nonprofit specializing in those issues. Contact: ddillard@hfa-usa.org

Join the conversation as a VIP Member