A baby boy's eyes changed colors after the coronavirus-infected child underwent a common COVID-19 treatment, according to a case study reported by Frontiers in Pediatrics, a medical journal that publishes research in pediatric care and children's health.

Published under the research topic "Childhood Vaccination and COVID-19," the April 19 case report, titled "Favipiravir-induced bluish corneal discoloration in infant with COVID-19," details the COVID-19 therapy's jaw-dropping effects on a six-month-old.

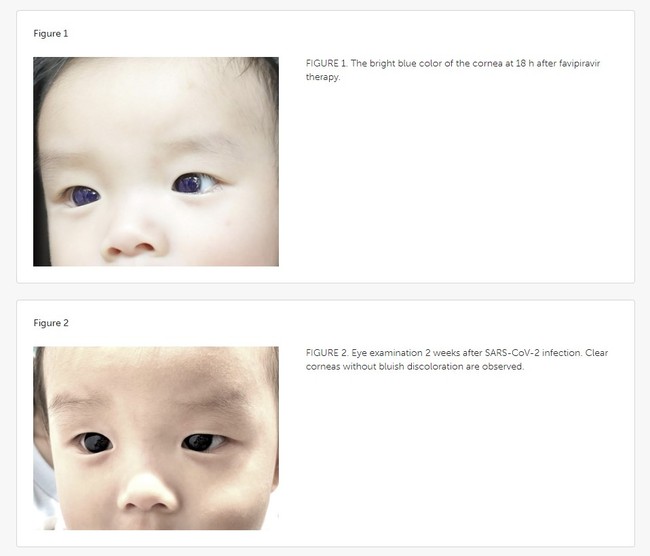

Before-and-after photographs of the coronavirus-positive child's eyes | Frontiers in Pediatrics

Before-and-after photographs of the coronavirus-positive child's eyes | Frontiers in Pediatrics

The study, conducted by clinicians at Chulabhorn Hospital in Bangkok, says that the Thai infant's dark-brown eyes temporarily turned "bright blue" overnight upon being prescribed and subsequently ingesting favipiravir, an oral anti-viral treatment recommended by Thailand's Ministry of Public Health's official guidance that was issued in 2022 for children with mild-to-moderate coronavirus symptoms. Marketed under the brand name Avigan, favipiravir is a Japanese anti-influenza drug produced by Toyama Chemical, a pharmaceutical subsidiary of the Tokyo-headquartered conglomerate Fujifilm. Singing praise, the Chinese government hailed favipiravir as "effective" with "no clear side effects," generating global excitement around the drug.

The Japan-developed drug, which some U.S. researchers consider "safe" for patient use, has been tested across several clinical trials in America, with the results being iffy, though it has not yet been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Recommended

Favipiravir (200 mg/tab) was prescribed as "first-line" therapy for the baby, the "youngest known patient" to receive the drug for COVID-19 infection, at a dose of 82 mg/kg/day on Day 1 and syrup (CRA Favi-Kids; 800 mg/60 ml) at a dose of 29 mg/kg/day on Days 2–5. Around 18 hours after the child started taking the COVID-19 medication, the baby's mother noticed the color change in his corneas, prompting the concerned parent to contact the pediatrician, who instructed her to stop the meds immediately.

About five days later, the discoloration faded and the baby's eyes returned to their original color. Doctors examining the infant found that his corneas were "clear" and "lacked a bluish corneal hue." No blue pigment "deposit" was observed on the surface of his irises or the anterior lens capsules and no evidence of fluorescence was documented when a cobalt blue (C-BLU) filter, used to capture fluorescein-stained corneas, was applied. Overall, the baby did not appear to have suffered damage to his vision.

Despite the "potential for adverse effects," the study notes, favipiravir remains the "mainstay" of oral anti-viral treatment in Thailand for children diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, in accordance with the Thai National Treatment Guidelines for COVID-19.

At least one other "unusual" case of color-changing corneas due to the drug's ingestion has been recorded.

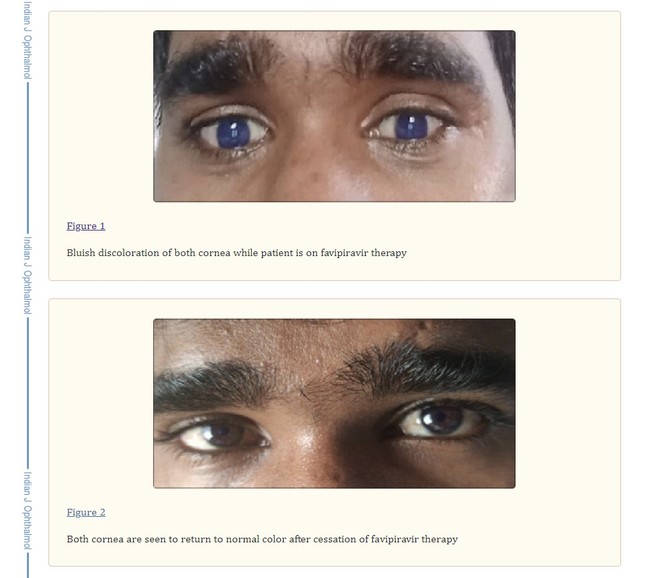

Two years ago, a coronavirus-positive man in India was reported to be the first instance of favipiravir-inducing discoloration of the patient's eyes. On the second day of undergoing favipiravir COVID-19 therapy (1600 mg favipiravir BD on Day 1 and the morning dose of 800 mg favipiravir on Day 2), the 20-year-old male's dark-colored eyes similarly became an electric blue, according to a December 2021 article that appeared in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Doctors advised that he terminate treatment, and his eyes saw immediate improvement, back to "normal" within a day's time. "It was remarkable to note that the very next day upon stopping favipiravir the patient's corneas returned to normal color," the report reads, "directly pointing" to the drug's usage.

Before-and-after pictures of the COVID-positive man's discolored eyes | Indian Journal of Ophthalmology

Before-and-after pictures of the COVID-positive man's discolored eyes | Indian Journal of Ophthalmology

There was no blurring of vision and the man's visual acuity was 20/20. Again, no pigment deposits were visible with no evidence of corneal thickening or fluorescence on the C-BLU filter. The lens and anterior chamber appeared to have clear contents as well.

"Also, despite extensive literature search, we could not find any case of bluish discoloration of the corneas. Hence, we report the first such case of bluish discoloration of corneas after treatment with favipiravir," the India-based physicians concluded the study.

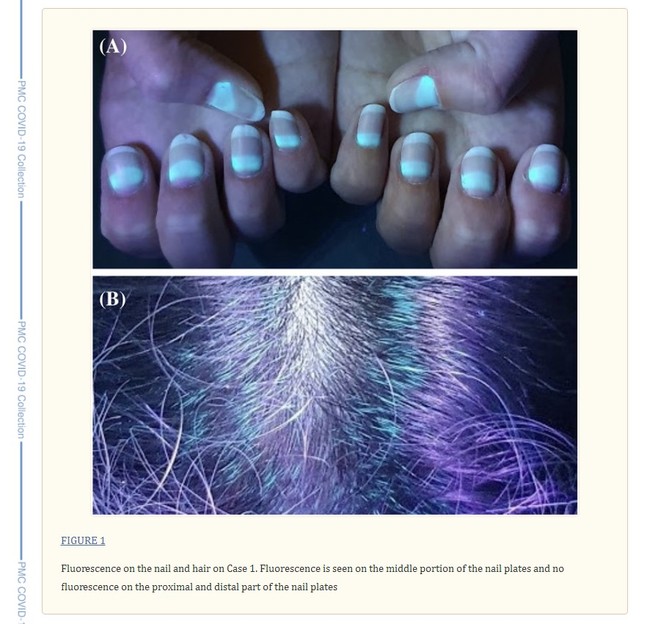

Favipiravir has also triggered fluorescence in human hair and nails, a winter 2021 Turkish experiment discovered, when seen under a Wood's lamp, which emits ultraviolet (UV) light. The study in Turkey warns that with high dosages of favipiravir, the substance may accumulate in tissues beyond hair and nails. Since the drug distributes in the kidney, lungs, spleen, and brain, "caution should be taken" when treating COVID-19 patients with co-morbidities like liver and kidney dysfunction, the study says.

Turkish study on favipiravir and fluorescence | PubMed Central (PMC) COVID-19 Collection

Turkish study on favipiravir and fluorescence | PubMed Central (PMC) COVID-19 Collection

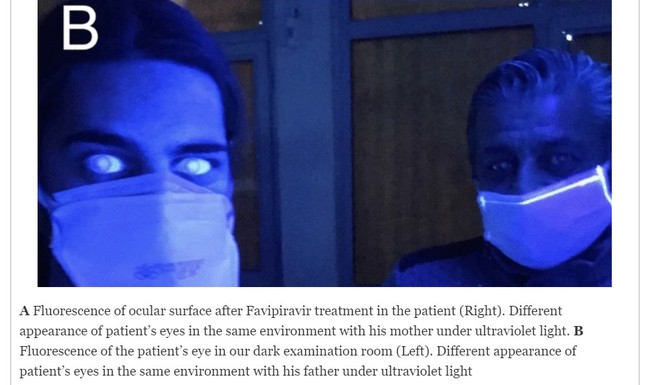

Also in Turkey, a 20-year-old photographer who contracted COVID-19, on Day 2 of favipiravir therapy, experienced blurry vision and blue-light reflection when he was exposed to UV-light sources at his workplace, a July 2021 Virology Journal entry says.

Aside from the visual impairment, the patient's eyes and nails appeared fluorescent under a Wood's lamp. Ocular-surface fluorescence disappeared after approximately 14 days of favipiravir treatment, but the patient's nail fluorescence persisted.

Photographs of the COVID-19 patient (left) taken under UV light | Virology Journal

Photographs of the COVID-19 patient (left) taken under UV light | Virology Journal

The ophthalmologists also demonstrated the drug's fluorescence by placing a favipiravir tablet under UV light.

A whole favipiravir tablet (left) cut in half (center) and dissolved in water (right) | Virology Journal

A whole favipiravir tablet (left) cut in half (center) and dissolved in water (right) | Virology Journal

Medical professionals have yet to identify favipiravir's long-term consequences and experts are still not certain why the med causes discoloration but suspect that fluorescence—the emission of light triggered by the absorption of electromagnetic radiation—"may be due to the drug, its metabolites, or additional tablet components such as titanium dioxide and yellow ferric oxide."

It remains "a mystery" whether the fluorescent substance is mainly caused by the drug metabolites or by the tablet's ingredients.

Favipiravir has a high absorption rate of ~97.6%. Laboratory inquiries, like the aforementioned, have examined the fluorescent characteristics of favipiravir, which signify "a direct relationship" between favipiravir's concentration and fluorescence intensity.

Similarly, a March 2022 dermatology case describes flecks of fluorescence that appeared in the whites of three coronavirus-positive people's eyes, as well as "chalk-white, crescent-shaped" glowing of the nails and "irregular spots" on the teeth, after the trio of healthcare providers working in the same ward of a hospital took a five-day course of favipiravir two months or so earlier.

Based on perceived potency and clinical efficacy, favipiravir is widely administered to treat COVID-19 around the world.

At the outset of the pandemic, favipiravir was first used against the coronavirus in Wuhan, China, the epicenter of the global COVID-19 outbreak. Favipiravir is currently commercialized for patient use in a multitude of Asian and European countries.

Favipiravir was tested in U.S. long-term care facilities as part of a Phase 2 trial to combat COVID-19 outbreaks in such settings. During the summer of 2020, the FDA granted a Canadian biopharmaceutical company clearance to proceed with its testing of 760 participants in elder-care homes. But, as of February of this year, the trial was terminated due to "recruitment challenges."

In spring 2020, Massachusetts hospitals launched the very first FDA-authorized trial of favipiravir within the United States.

Three hospitals including @MassGeneralNews and @BrighamWomens to launch first US trial of Japanese coronavirus drug. https://t.co/7y0AyhLeyG pic.twitter.com/wqmAh8y6co

— Mass General Brigham (@MassGenBrigham) April 7, 2020

"It's actually a very safe drug," Dr. Robert W. Finberg, the trial's principal investigator (P.I.) at UMass Memorial Health, told the Boston Globe. However, Finger admitted that pregnant women were excluded from the clinical trial, given evidence that favipiravir causes fetal deaths and birth defects among animals. Dr. Boris Juelg, the study's P.I. at Mass General, expressed apprehension in a Q&A concerning "teratogenicity," the ability to produce deformities in developing babies during pregnancy.

Recent research raises concerns regarding favipiravir's safety and effectiveness. A multi-center February 2023 trial in the U.S. concluded that favipiravir "lacked efficacy" and "should not be used" to treat COVID-19 patients. And, last year, a Stanford University study determined its data does "not support favipiravir at commonly used doses in outpatients with uncomplicated COVID-19," asserting that further research is "needed to ascertain if higher favipiravir doses are effective and safe."

A December 2022 pharmaceutical-toxicology study out of Istanbul, Turkey, called on researchers to extensively examine if favipiravir induces genotoxicology in cardiac and skin cells. Genotoxicology is the property of chemical agents that can damage genetic information (DNA or chromosomal) within a cell causing mutations, which may lead to malignant transformation (cancer).

Join the conversation as a VIP Member