"There's a lot of opposition to just hearing what President Trump has to say," Elon Musk said at the beginning of his two-hour interview on X with the 45th and would-be 47th president.

Musk noted, "I got a letter from the EU Commission, like, saying to not have disinformation during this discussion we're having. And there's a lot of attempts to do censorship and to force censorship even on Americans from other countries."

That's not quite right, but it's close. The letter was not from the European Commission but from EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton, a French citizen and former CEO of France Telecom. The letter purports to remind Musk of the European Union's Digital Services Act's requirements of "all proportionate and effective mitigation measures" regarding "detrimental effects on civic discourse and public security."

In other words, X must censor questions to and answers from an American presidential candidate and keep the EU informed of its censorship procedures. What must be censored? "The amplification of content that promotes hatred, disorder, incitement to violence, or certain instances of disinformation." Breton reminds Musk of "formal proceedings ... already ongoing against X under the DSA."

Nice little digital company you've got there. Wouldn't want anything to happen to it.

It would surprise the American founders not a little that the unelected head of a European multinational organization would feel entitled to demand the words of an American presidential candidate be censored and to be informed of the censorship tribunal's procedures and decisions.

Recommended

Some Americans, however, might not be surprised at all. They might think Breton is very much on the right track.

Case in point: At the White House's press briefing on Monday (the transcript is available on the White House website), Washington Post reporter Cleve Wootson said, "I think that misinformation on Twitter is not just a campaign issue. It's an America issue. What role does the White House or the president have in sort of stopping that or stopping the spread of that or sort of intervening in that?

"Some of that was about campaign misinformation, but, you know, it's a wider thing," he continued. Wootson didn't use the verb "censor," but his question suggested that the government had a moral obligation and a legal right to censor the opposition party's presidential candidate and to monitor what White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre described as "the responsibilities that social media platforms have when it comes to misinformation, disinformation."

One example of Team Biden's approach to "misinformation" was the successful attempt to enlist social media companies to suppress dissemination of the New York Post's Oct. 2020 story on Hunter Biden's laptop. Playing a key role was Antony Blinken, then a Biden staffer and now secretary of state, who organized the letter signed by 51 former intelligence officials or current CIA consultants charging that the laptop had "all the classic earmarks of a Russian intelligence operation."

Of course, Blinken's successful attempt to stamp out "disinformation" turned out to be, once the election was safely over, disinformation itself. But it got him the secretary of state job for four years.

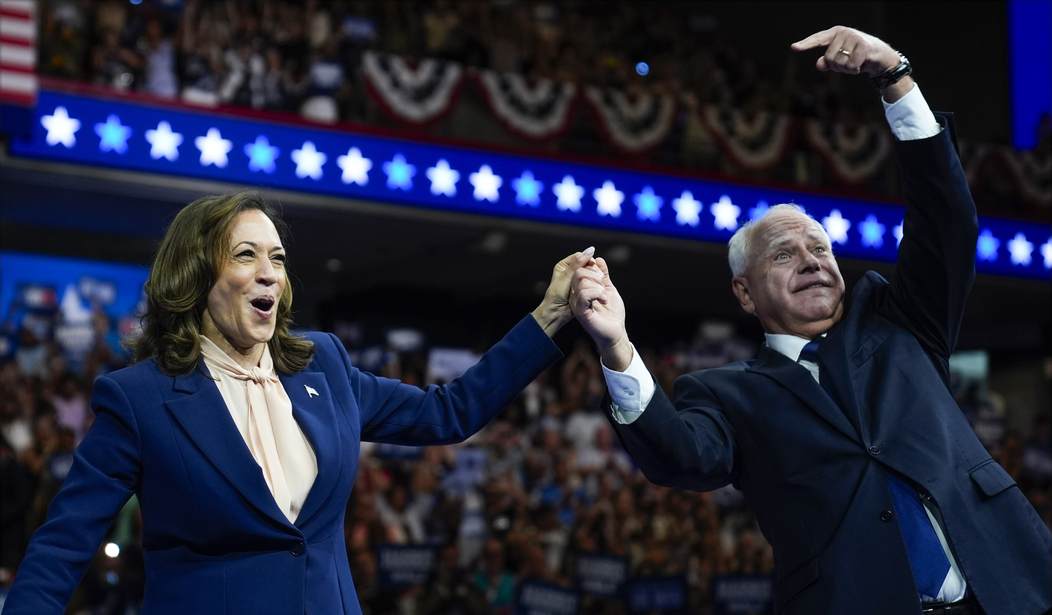

The public can expect more of the same if Vice President Kamala Harris is elected this fall. "There's no guarantee to free speech on misinformation or hate speech, and especially around our democracy," Gov. Tim Walz (D-Minn.), Harris' running mate, told MSNBC in 2022.

Liberals tried to excuse Walz on the grounds that he was talking about spreading false information about the dates and procedures of elections, and the First Amendment does not preclude remedies for fraud and libel. But the decision-makers in such cases are supposed to be neutral courts, not partisan officials.

But it is long-settled constitutional law that the First Amendment does indeed prohibit censorship of what partisan officials may believe, sincerely or self-servingly, is hate speech or misinformation. On the contrary, the remedy for bad speech, as Thomas Jefferson advised people more than 200 years ago, is more and better speech.

And no one should be reassured that Walz actually does understand the First Amendment by his campaign cries of "mind your own damn business" directed against, among other things, banning books. But the only reference to banning books in recent political discourse has been Gov. Ron DeSantis' (R-Fla.) law barring sexually explicit books in school libraries from kindergarten to fourth grade.

Traditionally, in America, it has been people on the Right who have been most willing to ban books and restrict some personal behaviors. Today, and with the Biden-Harris and Trump-Pence administrations as recent examples, the greater threat to basic freedoms comes from the Left.

And not just from Breton and Walz. Harris' authoritarian instinct has been apparent throughout her career, as Dan McLaughlin argues persuasively in the National Review, citing her efforts to disclose nonprofit groups' donor lists, her prosecution of a journalist exposing Planned Parenthood employees' sale of fetal body parts, and her proposals to issue executive orders to ban certain guns, set drug prices, and rewrite immigration laws.

The public can count on a vigilant adversarial press to expose any violations of basic freedoms by a Trump-Vance administration. Judging from the press' complacency with Harris' refusal to undergo interviews or to say anything about public policy, it cannot count on the same if the Harris-Walz ticket wins.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member