This year is the 50th anniversary of Richard Scarry’s terrific picture book, “What Do People Do All Day?” It’s also the 70th anniversary of Candyland, which Eleanor Abbott designed in 1948 after she contracted polio in San Diego and sought something to delight the children in her hospital ward.

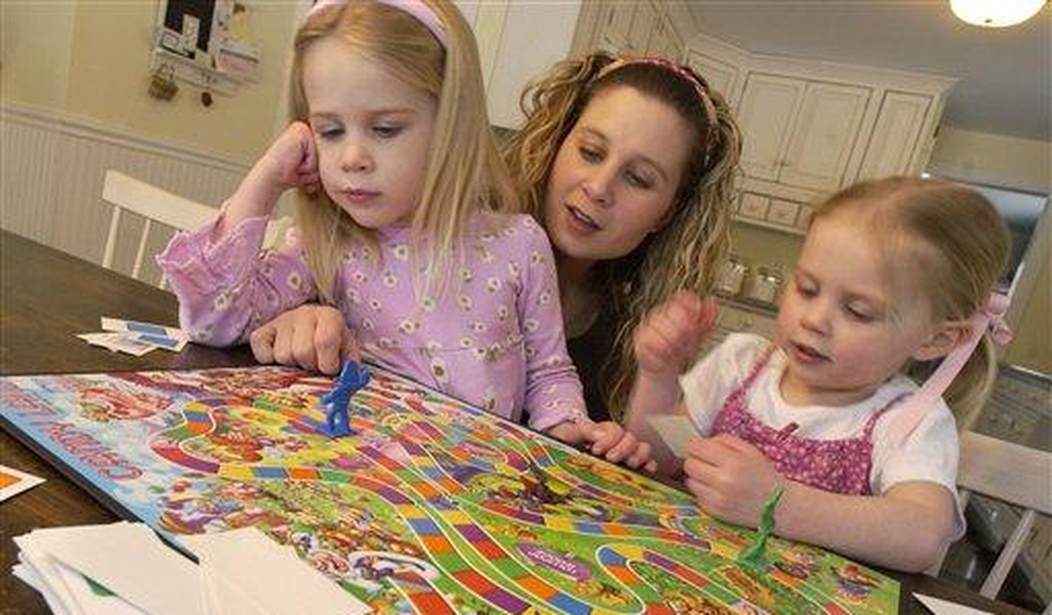

Candyland still sells about 1 million copies per year: It’s for ages 3 and up, and especially appropriate for members of Congress, since it requires no reading and minimal counting skills. The 1967 edition of Candyland that I recently played with a granddaughter includes these instructions: “Due to the design of the game, there is no strategy involved. Players are never required to make choices, just follow directions. The winner is predetermined by the shuffle of the cards.”

I appreciate theological predestination, but Candyland’s “predetermined” outcome regarding winners and losers sounds like something from a plaintive Bernie Sanders speech. Furthermore, movement to that predetermined outcome is super-erratic: A child or politician can be moving steadily through the red, green, blue, yellow, orange, or purple spaces, only to pull a card that drops him all the way back to Peppermint Stick Forest. That happens in life, as Job realized and cancer victims learn, but it’s atypical.

Compare Candyland’s teaching to the economic wisdom of Richard Scarry (1919-1994), a writer and illustrator who published 300 books that have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide. He drew charming pictures of anthropomorphic animals (including cats, rabbits, dogs, and goats) who live in Busytown where everyone works. Everyone is both giver and taker.

One story in “What Do People Do All Day?” begins, “Farmer Alfalfa grows all kinds of food. He keeps some of it for his family. He sells the rest to Grocer Cat in exchange for money. Grocer Cat will sell the food to other people in Busytown. Today Alfalfa bought a new suit with some of the money he got from Grocer Cat. Stitches, the tailor, makes clothes. Alfalfa bought his new suit from Stitches.

Recommended

“Then Alfalfa went to Blacksmith Fox’s shop. He had saved enough money to buy a new tractor. The new tractor will make his farm work easier. With it he will be able to grow more food than he could grow before. ... What did the other workers do with the money they earned? First they bought food to eat and clothes to wear. Then, they put some of the money in the bank. Later they will use the money in the bank to buy other things. ... Grocer Cat bought a new dress for Mommy. She earned it by taking such good care of the house. He also bought a present [a tricycle] for his son, Huckle. Huckle was a very good helper today.”

Richard Scarry showed that good economics and good writing go together. Children at first believe in magic: Food, clothes, and houses just appear. Writers who use the passive voice minimize human responsibility: ‘Mistakes were made.’But Scarry fills “What Do People Do All Day?”with the active voice. He teaches that people who work hard make things appear, as in this story about building a new house:

“Huckle lived with his Mommy and Daddy in a part of Busytown where there were no other houses nearby. ... Then one day a man came and dug a hole in the empty lot next door. ... Jason, the mason, made a foundation in the hole for the house to be built on. His helper mixed cement to hold the bricks together. Sawdust, the carpenter, and his helpers started to build the frame of the house. Jason started to build a chimney.”

Note the active voice even regarding stuff that becomes invisible: “Jake, the plumber, attached the water and sewer pipes to the main pipes under the street. They put in water pipes. ... The electrician attached electric switches and outlets to the wires. Sawdust nailed up the inside walls. The walls covered up all the pipes and wires.”

Scarry occasionally lapses into the passive: “Water is used to put fires out.” But he’s enormously superior to Venezuelan Marxists who never realized that oil revenues and other products don’t just appear magically: They have now bankrupted what was the wealthiest country in South America. Will our grandchildren vote to live in Candyland or Busytown?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member